Posted March 16, 2013

Posted March 16, 2013

Posted March 16, 2013

March 8, 2013

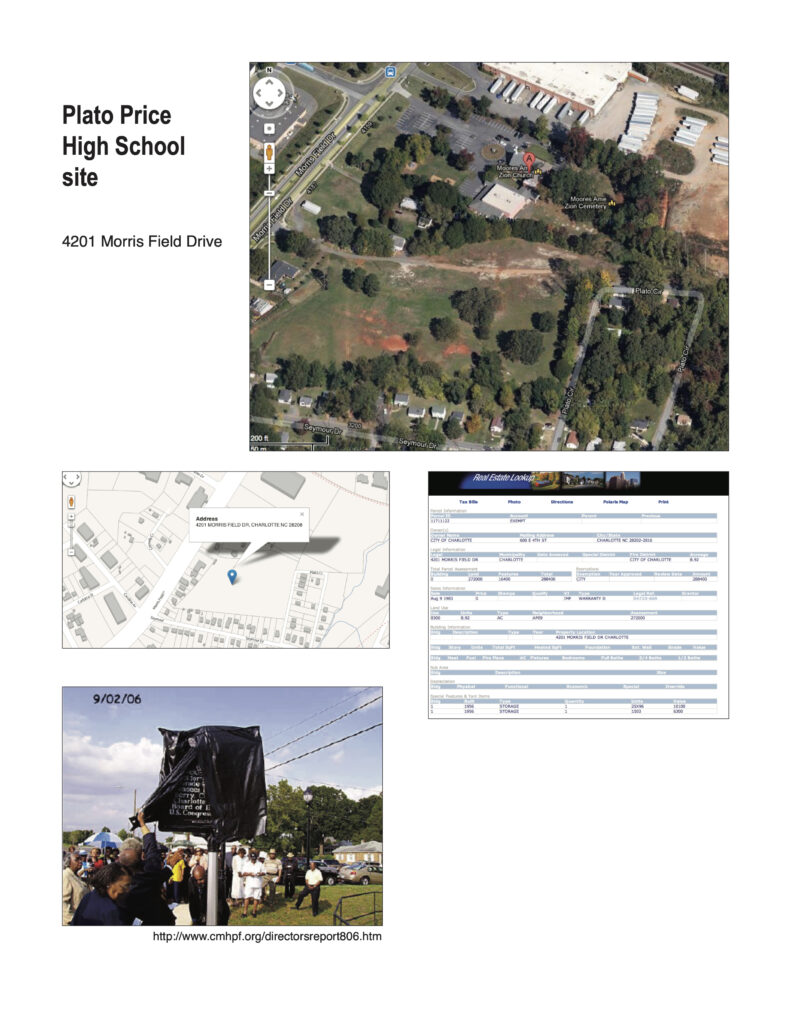

This school is on the tour of sites that illuminate community leadership strategies because of a young student bus driver who used the threat of a work stoppage to call into question the school system’s bypassing black schools in favor of white schools when new school buses were to be parceled out to the drivers.

The student’s name was Mel Watt, who as an adult went on to serve in the U.S. Congress from the 12th District. He told the story of the boycott threat to C-SPAN in 2005. An excerpt:

“So, and I led in my junior or senior year, I led what was threatened to be a boycott of black school bus drivers, because we knew that some new buses were coming into the system, and we wanted one of the new buses. So, we basically threatened not to drive. We would just strike, basically.

“And finally, they gave us one of those brand-new buses. And, of course, they punished me. They said, you know, we’re not going to let you drive it. I said, fine. You know, this is not about me driving it. They gave it to somebody else to drive, but that was fine.”

Read a longer excerpt of Watt’s comments about Plato Price here.

As mentioned in Watt’s interview, the school closed in the 1960s as the CMS school board desegregated schools mostly by closing black schools and busing those black students to formerly all-white schools. Around 1980 the school’s auditorium in the center of the school was used as the district depository of used books, while classrooms were used for other storage.

Plato Price opened opportunities to many African Americans. For students unable to reach Second Ward High, it afforded access to a post-primary education. Many of its students, Mel Watt among them, were bused sometimes many miles past segregated white schools. A number of Plato Price graduating classes have active reunion committees and a presence on Facebook and classmates.com.

But the school’s history illuminates an era of separate-and-unequal education in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

One example: It wasn’t until 1961, more than 40 years after children went to school on the site, that CMS petitioned to hook the school up to sewers.

The site is on what was once called Dixie Road but is now in the 4200 block of Morris Field Drive near the airport. Aerial photos and real estate maps mark the spot, and illuminate the references on the Moore’s Sanctuary AME Zion church website to the neighboring school and its importance to members of the church, which has been in the same location since the 1870s. A school building has been on the site since 1915.

In its report focused on Torrence-Lyttle School in north Mecklenburg, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission wrote this:

“The North Carolina Legislature passed legislation in 1913 that enabled counties to issue bonds to build high schools for African American children. It was not until 1923 that the City of Charlotte opened its first high school for African American children, Second Ward High School.

“In 1936 Mecklenburg County approved the construction of four rural high schools for African-American children: Pineville Colored High School, Plato Price High School (West Mecklenburg County), J.H. Gunn High School (East Mecklenburg County), and the Huntersville Colored School.” (http://www.cmhpf.org/TorrenceLytleRFP.htm)

According to an “historical overview” of Rosenwald schools in Mecklenburg County written by Thomas W. Hanchett, the Plato Price building that Mel Watt attended was built in 1937. Hanchett says about the four schools:

“The one-story brick buildings were built too late to receive Rosenwald construction money, but their architecture showed the program’s lasting influence. In each structure, classrooms lined a main hallway and at Pineville an auditorium projected to the rear, designs modeled closely on floor plans #60 and #7 published in S.I. Smith’s 1924 Community School Plans.”

The City of Charlotte took ownership of the school site in 1983, and demolished the school sometime during the 1980s. The land was used by a contractor for some years, but more recently has been vacant.

In 2011, more than 40 years after Plato Price School closed, Habitat for Humanity petitioned for ownership of the site to build more than 80 Habitat houses. On March 7, 2013, the land remained unused and undisturbed.

March 8, 2013

Jim Polk, in the red sweater above, led a group of friends in the late 1950s in the Grier Town community of Charlotte. They operated under the banner of the Eastside Council on Civic Affairs.

Their successful effort to extract justice from city officials was done privately. To this day, few of the residents of Charlotte know the history.

For a Black History Month presentation at the Tuesday Morning Breakfast Forum in 2007, Polk and the other surviving members of the Council told some of their story. The original of these words is on the Forum website.

– – –

Feb. 28, 2007

A small group of average black citizens “created a movement” in late-1950s Charlotte by insisting not only that it was time for equal services but that it was time for whites in positions of power to sit down with blacks as equals.

Several original members of the Eastside Council on Civic Affairs met Tuesday with the Tuesday Morning Breakfast Forum to outline their work. Led by Jim Polk, the group talked about their methods, their successes and what they see as the long-run positive impact of their experience.

Unlike the more widely known civil rights struggles that focused on nonviolent protest and public shaming, Eastside Council members took the private route. Promised that there would be no publicity, powerful whites sat down with Council members and heard out the group’s complaints. Change followed, first to equalize levels of garbage collection between white and black neighborhoods, then at job sites as the group focused on breaking down barriers to employment.

All those present at the Tuesday Forum are named in the photograph above. Excerpts from the comments:

Jim Polk: “A group of guys in Grier Heights would come together and talk about what we considered some problems and some opportunities in the community. We met and talked about things like education, beautification or other concerns of the community, and things we heard people talk in the community, their desires and their goals and aspirations. And we tried to work on those things.

“I guess one of the things that really launched us, if you will, was a program that we started working because of sanitation problems. Sanitation in this case was that we discovered that across the creek from us, which was Myers Park, the garbage man would drive up, go in the back of the house, pick up the garbage can, and go back to the [truck]. So they were getting full service. And we felt, why were we not doing it, because they ask us to roll our cans out the street for pickup. So we talked about why should we not have the service, and we were taxpayers. And most of the guys in the group at that time were homeowners.

“And we started to explore that and do some checking and talking to people and talked to the then-city manager and other people. And the result was that they said OK, we will start collecting your garbage in the rear of your house provided you have a can that will meet regulation. So we made sure we bought the right sized garbage can so there would be no problem with that. And that worked out.

“What that amounted to at that time early on was: As you know, in order to get groups going or to work with people, you really need a “stop-sign victory” to get something going and to continue. As Paul Jones, a former Model Cities director here used to say, You need to do something with high visibility and early impact. People will work together, they will believe they can make something happen, and they will carry on. So that was our stop-sign victory.

Polk: “It was effective, so much so, that a number of guys on the westside said how did you guys do that – we need to know how to make that happen. And they formed a group over here similar to the Eastside Council. We met with them and talked about how we got this whole thing going. And they in effect started to talk to the city about – results being that in the black community in Charlotte they were getting the same services that all other citizens in Charlotte received. And rightfully so….

“After that we realized what was required to make some things happen. We started to do what we called, ‘the man in the chair.’ The man in the chair was bringing together folk in the city of Charlotte who had political clout or whatever was necessary to make some things happen.

“It was a conference held in Willie Davis’ living room around two card tables and some folding chairs. And we would reserve at the end of that table the guest for the night, and we would talk with them about the things we thought they ought to know from us.”

Willie Davis: “We came to believe you can get things done by going directly to people who are responsible for what happens in the community. He mentioned the man in the chair: We realized that the people who were making the major decisions had not taken the opportunity to talk to all the community, but just that part of the community that they thought was important. On the other hand, and some of us are aware of the fact that God used ordinary people, and we had ordinary people. The people who made up this Eastside Council on Civic Affairs – and we took that name because we were interested in doing things across the spectrum; we were not going to focus on any one thing, so we called ourselves the Eastside Council on Civic Affairs.

“We realized that we could go to people and the only thing they could do is say no, we don’t want to talk to you, I won’t talk to you. So what happened: we started going directly to individuals. We started with the garbage situation, realized this is working, and started calling someone else. We’d get on the telephone, call individuals and said to them, I’m calling from the Eastside Council on Civic Affairs, wonder if you will sit down and talk with us. By that time they recognized that this person was doing something outside the box, but nevertheless it must be OK – because I was calling from my job, and my job was where I was not supposed to be calling from. And they knew exactly where I was calling from. They knew it must be more than an everyday call.

“I promised them, OK, if you come and meet with us there will be no press, no one will know about it. Just come and meet. So at the meeting they would probably get there at nine-thirty, ten o’clock.

Malachi Greene: “Let me say this: At the time there were no black people in the quote power structure of the city of Charlotte. So we’ve got a bunch of black people calling the white members of the power structure asking them to come sit in this chair. We don’t know any other place in the country where things happened like that.”

Davis: “There’d be only one person. Just one person outside the council would come meet with us. I don’t remember ever calling someone and, by the end of that conversation they telling me no I won’t come. Now, I might have to talk three or four minutes before they would agree, but they would come because they had the assurance that it’s OK, you’re not going to tell anyone I came.

“So the meeting would get started about nine o’clock. They would drive up around nine o’clock. We were just sitting there around the table, waiting for them to come. And they would come in … yes, nine at night, so they could leave their community, and go back to their community.

Greene: “Without anybody knowing that these white power guys, rich white men, powerful men, had gone to a black community to see, to be regaled by a bunch of black guys.”

Davis: “In an article over there, some of the people who attended included John Belk, Jim Whittington, who was the mayor pro-tem, the superintendent of schools at that time, Craig Phillips…. J. Ed Burnside was at that time president of the Chamber of Commerce and was a banker, the mayor, Stan Brookshire at that time; Dr. Louis Patrick, who was pastor of Trinity Presbyterian Church and was pastor to many people of influence. David Gillespie was one of the editors of the Charlotte Observer and a former editor of the Gastonia Gazette; and Dr. John Cunningham, president of Davidson College….

James Ross: “To put this in perspective, we’re talking about 1950-something…. What’s important about these guys meeting someone? What we’re talking about something that was unheard of in these United States … asking to sit down as equals.”

Greene: “What this said was that you got a group of people who decided that they were going to make a difference. They were going to change this thing. And they were persistent. Understand, there was no black city council person, there were no black school board members, no black county commissioners, no black nothing. No executives at the government level or at the private level….”

Davis: “We had no persons who had a lot of money. On the other hand, we had some guys who felt, I’m as good as anyone else, so let’s sit down and talk. When you look at the backgrounds of people, we all had one thing in common: We were all from Griertown, but that was about the only thing… no black persons of influence.

“People would sit down with us, and it was not always a friendly exchange. We were very direct. In fact, there were times when people might have felt that ‘you fellows must think that you are something. Who are you to tell us what we ought to be doing?’

“We only knew we were taxpayers. But we knew what they were doing across the creek….

“When I would go in the principal’s office, I was working at AG [Alexander Graham Jr. High]. They finally allowed a black person to come and work at a predominantly white school. So I would go in there, leave my classroom, get on the telephone and call and talk to these persons… And we would go from one person to another. And many of them would say, Who are you guys to tell us what we ought to be doing?

“At one of our meetings we got this thing, ‘I can’t find people who are qualified to work. I would hire somebody. So we’d say, OK, let’s get started. That moved us into the formation of the bureau….

Polk: “These guys that we named, and some others, would go back downtown, and they would talk about having the experience in the chair. We learned that. We were told. They’d talk – it got to a point that in Charlotte North Carolina, among the hierarchy, the chamber guys, all those guys would say, ‘If you are a white man and you haven’t been in the chair, you don’t amount to much in Charlotte. [laughter] They said it, we didn’t.

“It was interesting. You’d get some subtle feedback and you’d learn what was going on….

Polk: “Others heard about it. The Southern Regional Council printed some things about it, to the extent that others outside the community heard about it. And we were fortunate that a guy who was writing an article for Harper’s Magazine stopped in Charlotte and learned about what was going on and finally met with us. And as it turned out it was Phillip Stern, who was one of the Stern family members of the Stern Family Foundation. To make a long story short, after some calls from New York and Washington and back and forth, the Eastside Council ended with a grant of $60,000 from them to start what was probably the first or second community manpower training program in America. About the same time Leon Sullivan was starting up OIC in Philadelphia [Opportunities Industrialization Center, Inc.]. It is interesting that of course we didn’t know what this was all about. The executive director of Stern lived in New York, and visited with us one time and brought down a guy from New York University. On an envelope we kind of diagrammed and set out a manpower training program. And that was putting together the elements, and use of the Department of Labor and private funds and all the federal funds directed toward employment and training. And that was the kickoff of the Charlotte Bureau of Employment and Training.”

Greene: “Instead of using a welfare approach to economic uplift, the approach was economic development. It was jobs. It was developing entrepreneurs and businesses. I found that to be unique in running around the country looking at stuff….”

March 18, 2013

This incident in Charlotte’s history has been chronicled elsewhere. But it may be a reminder that, in William Faulkner’s original words in “Requiem for a Nun”:

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Or in presidential candidate Barack Obama’s paraphrase in his 2008 “A More Perfect Union” speech, “The past isn’t dead and buried. In fact, it isn’t even past.”

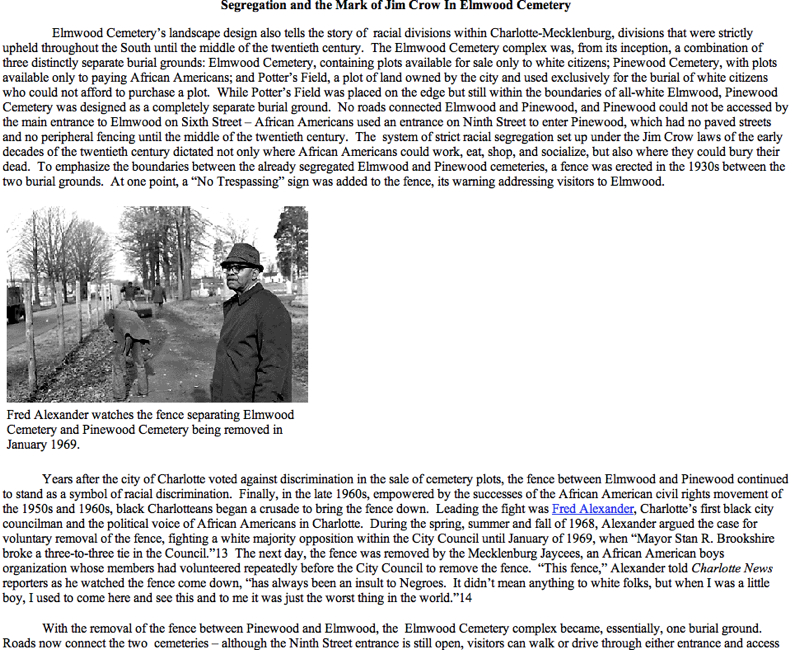

Elsewhere on the Landmarks Commission site are these words.

The Fred Alexander papers are in the UNCC Library’s Special Collections. See particularly Box 14 Folder 29 on the Elmwood/Pinewood cemetery.

Feb. 26, 2013

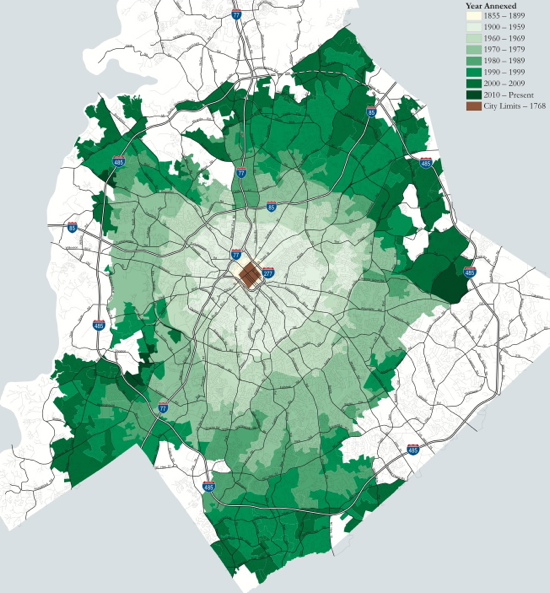

George Washington called Charlotte a “trifling place.” Even if to many people it remains a trifling place, it certainly is a bigger trifling place.

The city has taken full advantage over the years of North Carolina annexation laws. Cities are the subservient creatures of the state. But the theory behind the N.C. statute over the years has been that places in North Carolina that are urban in nature should be municipal in governance.

How to quantify the definition of “urban?” North Carolina has traditionally depended primarily on a count of the number of residents per given quantity of real estate. But to that base there have been some additional standards. This is not the place for getting into those weeds.

The motive was in part financial: Urban areas would demand additional services, so give the nearby city the power to tax and the responsibility to provide those services.

The effect has been to allow Charlotte to absorb the subdivisions and other development built at the city’s edge, to have the resources to provide the services urban residents required, and through zoning to have a say in how developers used the land that would one day be inside the cit.y

In the Charlotte map above, the speck in brown marks the size of the city in George Washington’s day. The subsequent annexations are in ever-deeper shades of green. In JFK’s day, I-85, Park Road Shopping Center and Eastland Mall were all outside of Charlotte. SouthPark was a cow pasture.

The development community during the 20th century had a large, some would say oversized, say in the city’s development. Whatever the truth in that regard, it is undeniable that city policy until the very end of the 20th century favored low-density, auto-dependent suburban development.

Compared to a city like Greensboro, Charlotte was late to the party in development a road system that would serve multiple employment centers. Until the 1970s, essentially all traffic arteries were spokes of a wheel emanating from George Washington’s Charlotte. Even in 2013, the bus system mirrors that dominance of spokes, forcing most long-distance bus riders to go downtown to transfer.

Source: Download Planning Department’s annexation map in PDF

Feb. 26, 2013

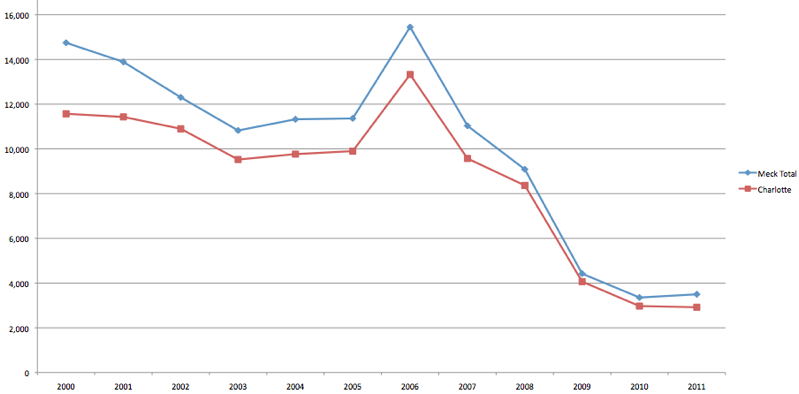

This may be more than a local map to the Great Recession. Note that the proportion of Mecklenburg County permits issued in the Charlotte zoning sphere of influence has become larger as a result of the recession.

If that trend continues, the gap would suggest that more housing units — both multifamily and single familly — will be urban than suburban. Another factor: Most of Mecklenburg that Charlotte can annex has already been annexed. Developers wanting near-but-not-in Charlotte projects will increasingly go outside Mecklenburg.

Source data here.

The door opened a bit more on public policy discussion in Charlotte-Mecklenburg today with Supt. Heath Morrison’s decision to order all of his 22 task forces to meet in public after the first organizational meeting.

Asked why the change, one task force co-chair said, “It was the right thing to do.”

A jaded public has reason to know that it being the right thing to do is rarely a sufficient reason. Perhaps Morrison will clarify.

The Observer’s Ann Doss Helms’ report on how longtime CMS critic Tom Davis valued the feedback from folks who were able to sit in the back of the room as an earlier citizen committee met and Davis was a member of the committee.

As I wrote last week, it is incumbent on the task forces to “find new ways to share your deliberations with the public. Be imaginative. Call on your friends to get the word out.”

Democracy is messy, and building consensus in this community on anything schools-related is even messier.

But until that work is done, Morrison will be unable to act. These task forces, if they are to be useful, should be cauldrons of controversy out of which consensus can be formed. No, this is not work for the timid.

And it is not sufficient that task force members come to agreement amongst themselves. That is only the beginning of the task.

The goal, clearly, should be to nurture community consensus by taking the community along for the ride — giving the community a good, blow-by-blow, thorough airing of every side of every controversial possible solution to whatever issues a particular task force attempts to address.

There’s no better way to do that than to produce lots of information about the discussion.

I would hope that every visitor to a task force meeting would be encouraged by the task force co-chairs to write about what they heard while they were visiting. I would hope that every member of every task force would be writing or skyping or videotaping their reflections after every meeting and putting the material not in a binder or a shoebox but on a publicly accessible website.

And I hope that every task force avails itself of the Internet and social media tools to share its information directly with the public.

No CMS problem has ever been caused by an excess of accurate information.

– Steve Johnston

Jan. 10, 2013

At tonight’s school board meeting, Supt. Heath Morrison announced an online tool to allow parents and others to share ideas with the task forces named to help design the district’s strategic goals. There are 22 such task forces. I’ve sent every task force the following message:

At your first meeting, please establish that all future meetings of your task force will be open to the public and that the public will be notified of your meeting times and places in accordance with CMS policy.

To bring the disparate interests associated with CMS together, we as a community must air issues thoroughly, allow fact-finding and vigorous debate, and then build consensus around what may well be a compromise position that honors the complexity and diversity of this district and its people.

Your modeling of behaviors like transparency, candor and openness will help the community move away from its confrontationalism, and contribute to an environment in which the superintendent’s ultimate recommendations can gain a foothold.

Indeed, Heath Morrison probably doesn’t need your ideas; he already has lots of those. What he does need is a way to move community members away from apathy or obstructionism or me-first-ism. Your task force can contribute to that by carefully airing in public all sorts of proposals related to your topic and then gauging public response.

Most citizens with a vital interest in your discussion will never attend your meetings, of course. And neither CMS nor media has the resources to “cover” every task force. So it is imperative that you find new ways to share your deliberations with the public. Be imaginative. Call on your friends to get the word out.

This is just one of many websites that one or more task forces could use without cost to share information about its proceedings. And there are lots of offline methods of sharing information. I hope each task force will find a suitable tool.

Dec. 20, 2010

Sunday’s Observer editorial page began a two-week focus on citizen comments on “what would make CMS a great system.” Comments are below.

Mike DeVaul

Senior Vice President, organizational advancement, YMCA of Greater Charlotte

“If it takes a village to raise a child, then why does it not take a community to educate one? In my view, a great public school system focuses on its core services and engages community partners to ensure that all students have goals beyond high school graduation. I believe that Success in school, work and life for any individual depends on a “network” of support (school, parents, mentors, extracurricular and enrichment opportunities) that nurtures his or her their potential.

“First, we need shared accountability for learning. At the Y, we are determined to make the best use of a child’s out-of-school time with activities that develop character and social skills, provide academic support through tutoring and connect students to positive role models. By opening the doors of communication between schools, businesses and organizations like ours, we could all have a better understanding of each child’s specific needs and challenges and would be better equipped to work with parents and teachers to have greater impact on academic performance.

“Second, I believe that greater emphasis on kindergarten readiness and post-graduation vocational study could significantly increase our kids’ success rate. Could public and private business work together to re-invent the education system to one that started in pre-kindergarten and supported kids through age 20?

“We also need to nurture strong parental support. Not by judging their abilities or intentions but by providing true supportive help. We have adults in our community who have felt disenfranchised by a public school system since their youth. Lacking the chance to connect to their own education as children, they have greater difficulty connecting now. The school system needs more volunteers to help foster and strengthen good parental navigation skills. Most of our challenge lies in some parental inability to understand the system. Instituting a parent mentoring program in our community could utilize parents with good navigation skills to help their neighbors make better decisions for their children. We stand ready to assist.

“Lastly, as part of a cause-driven nonprofit that believes structured, enrichment activities truly help children learn, grow and thrive, I believe that every child should have access to out-of-school programs such as swimming, creative arts, dance, team sports, after-school programs and camp. Again, through collaboration with schools, businesses and organizations like the Y, and with the support of citizens who give their volunteer time and resources, we can provide year-round and lifelong structure and support that every child needs to succeed.

“The YMCA has been working in concert with our National Office for several months re-engineering our programs the better support educational outcomes. We stand ready to be an even stronger ally with our schools and others. We are better together, it takes a community to educate a child!”

Ericka Ellis-Stewart

Parent, civic activist

“A great public school system is one that is focused with laser-like precision on the business of educating children. It is a system where in which our community can rest assured that all children will have the opportunity to live up to their potential regardless of their geography, race, or socio-economic status. Simply put, each student has the opportunity to interact with and learn from a highly qualified teacher every day.

“A great public school system is one that is ripe with options that allow students to flourish academically, socially, and emotionally. It provides a plethora of opportunities for traditional and specialized learning that are geared towards challenging young minds to become critical thinkers and the leaders of tomorrow. Its daily goal is to change the life of a child for the better at every intersection.

“A great public school system creates a culture and environment of dedication and passion for teaching. The evidence of Learning is palpable in every corner of the schoolhouse. Teachers make learning come alive inside of the classroom. Principals are inspirational leaders and change agents. Parents are involved and highly visible. Educators are leaders in innovation who are valued and compensated for the contributions they make. Teachers no longer have to beg for reams of paper and hand sanitizer, or teach all day without a planning period.

“In a great public school system, all schools throughout the district produce academically successful and globally competitive students who are prepared to enter college or the workforce upon graduation. Every school becomes a place where teachers want to teach and students learn. With the effective use of technology, learning is made applicable and relevant to real-world issues. Throughout the district, there is a strategic focus on recruiting, developing, and retaining dynamic and skilled educators. Each classroom has a qualified, and capable , and experienced teacher.

“In a great public school system, each child has a strong foundation in reading, writing, mathematics, and science. All students are bi-lingual; fluent in English and at least one foreign language before entering high school. Music, arts education, and physical activity are no longer spare parts, but key components of the school day. The educating of our children becomes about more than teaching to the test. It becomes focused on a child’s growth, learning and development. School calendars are no longer tied to our agrarian roots and limited to only 180 days. School days are extended to provide children with more instructional time, if necessary. Achievement gaps become non-existent, and graduation rates soar, and no child is left behind.

“In a great public school system, as a community, we commit our resources equitably and efficiently to ensure that all children become well educated, productive citizens. We are no longer satisfied with mediocrity or status quo. We demand continuous improvement and expect nothing less than overwhelming excellence. We must put children first and set aside our political and philosophical differences to become “the village” that it takes to educate every child in our community.”

Amy Farrell

Executive Director, Kids Voting Mecklenburg

“Imagine we are in the year 2020. Over the past decade, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools has become widely regarded – in our community, state and nation – as a truly great school system. Charlotte residents are proud of CMS. Parents are moving to Mecklenburg County to enroll their students in CMS. What made CMS great? How did we get here?

“In 2010, CMS faced significant challenges due to the economy, public perception and other factors. Teachers: unhappy. Students: discouraged. Parents: uninvolved. Politics: ugly. Between 2011 and where we are today, in 2020, that changed. What made the difference? Getting the students involved in determining the success, and future, of their schools and community. The steps were simple, and transformational:

“Civic learning was restored as an essential CMS priority. Instead of focusing only on math, reading and science with just a touch of civics, government and history in 10th and 11th grades, students were given dedicated time, resources and learning opportunities to begin the civic learning process in kindergarten and continue it through graduation. We understood that just as we must learn to read, write, add and subtract, we must learn how our governments and communities work, the roles of leaders and citizens, and the impacts of policies and decisions. That knowledge built interest, commitment and trust.

“Ownership of CMS and its future was shared with all students. Smart people recognized that all students have the po tential to be leaders, and gave them good opportunities to develop and practice their skills at school and in the community. It was clear that students cared and wanted to make a difference. They helped to evaluate teachers and give them thoughtful suggestions. They met with school and city leaders to make decisions and share ideas and solutions. They watched out for and encouraged one another, making sure that the class that entered 9th grade was the same class that graduated four years later.

“Students were given a permanent seat at the table. Having teens, even as unelected advisors, sitting alongside elected officials on dais during school board, county commission and City Council meetings kept the focus on students and the future. It gave young subject experts a chance to weigh in on the decisions affecting them. It significantly increased the quality and tenor of the political dialogue, which became civil and productive.

“So what happened in 2011 that kicked off this change? As a community, we struggled with scarce resources and difficult decisions. Then, it dawned on us. We had the resource the entire time: our students.”

Pamela Grundy

President, Shamrock Gardens PTA

“Marker-wielding kindergartners cover the Shamrock Gardens Elementary stage, intently coloring a set of circus posters. They work in clusters, some kneeling, some sprawled flat on their stomachs, chattering happily as they fill the space between the lines with bright and varied hues. Their faces vary too, ranging from palest white to deepest brown.

“Below the stage, parents and teachers sit amid the remains of a spaghetti dinner, going over learning games that families can play at home. They talk as well, exchanging smiles and stories.

“Our families have come to Shamrock Gardens by many different paths. Some of us have lived in Charlotte all our lives; others have traveled farther – from Minnesota, California and New York, from Africa and Mexico and Vietnam.

We also come from different neighborhoods – from the working-class enclaves of Plaza-Shamrock and the Park Apartments, as well as from the tonier settings of Plaza-Midwood and Country Club Heights.

“But our children are all learning together. And by working to support them, we are creating a new community at the intersection of our differences.

“In my ideal school system, events like our kindergarten dinner would take place all across the county, at a far grander scale than we have been able to accomplish at our small school.

“Rather than narrowing our educational focus to endless iterations of standardized test scores, our community would take a broader look at children’s lives, helping turn schools into anchors and meeting points for the neighborhoods and families that they serve.

“Public policy and individual choice would also work toward creating school communities that pull our children out of the isolation of race and especially of class, broadening every child’s experience and providing opportunities for the highest levels of excellence at every school.

“We hear a lot these days about great teachers and involved parents. But if children are to reach their full potential, they need strong communities as well to challenge and support them.

“These goals involve plenty of obstacles: cultural and language differences; the harried lives so many of us lead, no matter what our income; housing patterns that frequently divide those with means from those without. They would require all of us to put more of ourselves into our public schools, from struggling single parents to corporate executives.

“But they would also help us make our schools into the best kind of public institution, one that strengthens not only individuals, but also communities and a nation. There is a difference between a goal that seems for the moment out of reach, and one not worth pursuing. Piece by piece, we have been building this kind of community at Shamrock Gardens. Staff and parents at many other schools are pursuing similar ends. None of us is there yet. But many are further down that road than we were some years ago.

“Faced with great challenges, communities and nations can divide or unite. In these hard times, we need to follow the Shamrock kindergartners’ lead, and grow together.”

Lucille Howard

Civic activist and former CMS parent

“CMS Superintendent Peter Gorman recently told the board of education that school course offerings are largely determined by size, student interest and staff certification. But the board still voted to create several kindergarten through eighth grade schools and one sixth through 12th grade school.

“All are destined to have limited course offerings simply because there will be fewer students at each class level. Fewer students at each class level almost certainly equate to diluted and, therefore, fewer requests for languages, higher math, advanced placement and other electives that are standard in the large middle and senior high schools.

“Seven grades in a school with 1,000 seats (an average of 143 students per grade level), which has been approved for Cochrane Middle School, guarantees almost nothing for the students beyond grade level math, language arts, history, etc. Will any Advanced Placement courses be on the schedule for Devonshire Elementary and Hickory Grove Elementary students assigned to Cochrane? It’s already been presumed that students will be transported to Garinger High for any sports, band and extracurricular activities.

“A long-standing CMS goal to have equity in access to comparable educational opportunities no longer exists for students assigned to these K-8 and 6-12 schools. CMS appears to have evolved into three systems: one of low-poverty, high-achieving schools; one of magnets serving students with transportation and good “luck”; and one of high-poverty schools in low and middle income communities teaching only the “basics.”

“Is institutionalized, unequal public education by Zip code now acceptable? If this is so, must families who have the means leave these schools and communities in order to get an equal education for their students? Is this healthy? Is it moral? Is it legal?”

Tim Hurley

Head of Teach for America in Charlotte

“Consider this: In one elementary school, more than 90 percent of the students are proficient in both reading and math. Three miles away, in a different elementary school, only 30 percent of the students are proficient in reading and less than half are proficient in math.

“If you’re wondering where this is happening, you don’t need to look too far. Both of these schools are here in Charlotte.

“The unfortunate reality in our city today is that where a child lives is born determines the quality of his or her education – children growing up in low-income communities are not given the opportunities they deserve to succeed. Solving the problem of educational inequity may seem daunting, but we know it’s possible.

“Working in our city for the last two and a half years as the executive director of Teach For America’s Charlotte region, I have seen many teachers – some of them Teach For America teachers, others not – lead their students in low-income communities to academic success. These classrooms, where students are held to high expectations and fully invested in their education, demonstrate that economically disadvantaged students can succeed on an absolute scale.

“Having witnessed these teachers put their kids on a different trajectory, both in school and in life, I have come to believe that having more highly effective people throughout Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools – teaching in our classrooms, leading our schools, and making decisions within the district – is a critical part of closing the achievement gap.

“To do this, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, like any high-performing company or organization, must go out and find talent. If we want the best to work in our school system, we must be aggressive in recruiting them here. Then, we must develop them to be leaders and work hard to retain them. If we do this successfully, I think Charlotte can become a harbor of educational talent.

“This school year, there are 230 Teach For America teachers – recruited from many of our nation’s top schools and selected for their records of achievement and leadership – working in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. One of my top priorities is to ensure that these teachers lead their students to achieve at the highest levels, not only for their students’ sake but also because if they have a successful experience teaching in Charlotte, they are likely to stay and continue to work to expand educational opportunities for kids here. Today, there are nearly 200 Teach For America alumni living in Charlotte and 70 percent of them are working in education.

“In our city today, our students are doing their part – showing up to school ready to learn. Unfortunately, we, as a community, are not doing our part – providing all students with an excellent education. With a continued focus on recruiting talent – along with strong district leadership, support from businesses, and public will – we can ensure that every school, in every neighborhood, holds up its end of the bargain.”

Steve Johnston

Member of the nonprofit Swann Fellowship education advocacy group

“The CMS we all deserve would make every school a place where every local elected official, every top CMS administrator and every business executive would be delighted to have their child or grandchild enroll tomorrow morning.

“The CMS we all deserve would have twice the economic resources that it has today, because the adults of this community would have ended the centuries-old North Carolina legacy of vastly underfunding public education.

“The CMS we all deserve would not teach to the test but test after teaching.

“The CMS we all deserve would focus its energy on the child at the back of the room, the child at the front of the room, and every child in between. Personal education plans would not be an ignored legal mandate but a fundamental teaching tool for preparing every single child for what parent and child decide is appropriate for that child – whether college, trade school, work or military service.

“The CMS we all deserve would have nurses in every school treating illness first, knowing that every child must be healthy to learn.

“The CMS we all deserve would honor students as the first and best teachers of other students, whether their siblings or their struggling peers. And until the day that all children enter school equally prepared, it would ensure that every school contained the range of preparation found in the county’s population, so that all classes would contain students ready to teach. And of course if that’s the case, there will be inspired adult teachers delighted to be in every classroom in the system, bonus or no bonus.

“The CMS we all deserve would sacrifice its own convenience and once again hold board meetings in school cafeterias for the convenience of the people it serves. It would prevent the Jim Crowism in neighborhoods from poisoning school assignments. It would make every school a magnet school – one chosen by a parent as the best place for her child. And by capturing parent involvement that way, it will have made every school as strong as CMS magnet schools have traditionally been.

“The CMS we all deserve could be so easily made out of the CMS we have. Let’s get about the task.”